Welcome to the March issue of the Peripatetic Historian.

This Month:

Peripatetic Field Report: Falling into Japan

Book News

Culture: The Mandarin Road

Let’s get started…

Peripatetic Field Report: Falling into Japan

Deeply-rooted beliefs about Japanese attention to detail and perfectionism were shaken the afternoon I fell through the man-hole cover.

Prior to that unfortunate event, Japan had been confirming my preconceptions. Our Tokyo hotel was a model of harmonious perfection, from the spotless tatami mats (please remove your shoes at the hotel entrance and store them in the designated cupboards) to the elegant bathhouse in the basement.

Vigilant eyes policed this perfection. When, at the breakfast buffet, I randomly selected two apple tarts from a tray, an attendant scurried in behind me and rearranged the remaining desserts to restore harmony to the platter.

Before leaving Tokyo, a cleaning crew went over our train carriage with vacuums, brushes, and tweezers, ensuring that no trace of dirt would spoil our onward trip to Nagano. After buffing the interior to a factory-fresh gloss, they lined up outside the carriage and bowed to the passengers waiting to enjoy their labors.

We bowed back.

The attention to detail was awe-inspiring; I marveled at this society’s proximity to perfection.

Until the manhole.

Striding up a busy Kyoto street, threading through a slow-moving clump of tourists, I planted my right foot on a manhole cover.

Like a steel tiddly-wink, the cover tilted, flipped, and slid aside. My foot plunged into the void; I toppled forward like a logger-slashed Douglas Fir, smashing my thigh against the pavement.

It was a femur-shattering blow. I was lucky to escape with asphalt-scuffed hands, a dirt streak on my trousers, and a red face.

Nearly 63 years of life experience, thousands of manhole covers, and never a failure. Yet here, in perfection-focused Japan, I almost suffered my first broken leg.

Did the team of workers who installed this manhole cover line up and bow to the passing pedestrians when they completed the job? What about the local inspectors charged with monitoring the condition of the city’s infrastructure?

My illusions, like my trust of manhole covers, have been shattered.

Monkeys in the Mist

Here’s another surprise: Japan is cold in the winter. I knew that the northern island, Hokkaido, could be chilly, but even in the south—Tokyo and Kyoto—the late January temperatures dipped well beneath our Taipei norms.

This was especially true when we climbed away from the sea, up into the mountains that surround Nagano, home of the 1998 Winter Olympics. It is a frigid land, snow falling through dark cedar and pine forests.

What, you may wonder, induced us to leave the comfort of heated hotel rooms to tramp through this sub-alpine zone?

Japanese Snow Monkeys.

The Jigokudani Snow Monkey Park is built around a group of geothermal hot springs. Jigokudani (literally “Hell’s Valley”) is one of the magical places where the earth’s crust is thin, and sulfurous geysers remind us that a fiery pit seethes beneath our feet. And it is here, among the vapor plumes that we found these famous animals.

The monkeys are a leading tourist attraction. Hoping to beat the crowds, we stayed in a nearby village (Yudanaka) and set off early to reach the park as it opened (9:00 a.m.). We timed our arrival perfectly. A thirty minute hike on a packed snow trail brought us to the river bank in time to see the resident monkeys sauntering down from the surrounding hills.

Jigokudani is a wildlife refuge forged out of interspecies conflict. These monkeys once ranged widely through the mountains, but a booming ski industry led to clear-cuts and new ski resorts. The habitat destruction reduced the natural food supply; the monkeys moved out of the mountains, invading lowland farms in search of sustenance. This produced a predictable response from local farmers: they began shooting the primate pests.

In 1964, Sogo Hara, a Japanese railroad worker, proposed a refuge to protect the animals and keep them away from “civilization.” Thus was born the Jigokudani Monkey Park.

The park is not fenced—the monkeys could leave at any time. To encourage their continued residence, the staff spreads a mixture of barley, soybeans, and diced apples across the snow every morning. This morning feeding was underway when we reached the park. Monkeys gamboled across the snow banks, gathering breakfast like teenagers picking strawberries.

Although free range monkeys possess undeniable charms, their adoption of Japanese bathing customs launched their careers as international celebrities.

After the park’s foundation, curious monkeys began to wander down the river to Korakukan Inn, a traditional bathhouse that had served customers since 1864. Inspired by the sight of humans taking the waters, the monkeys decided to join their cousins. This produced a fresh round of consternation, an uproar that was resolved by the construction of a “monkeys-only” bathing pool in the park.

Species-segregated bathing is a reality in Japan.

It also draws vast crowds of tourists eager to view this unusual behavior.

On the day of my visit the monkeys did not disappoint. Breakfast complete, the younger members of the troupe entertained the human observers by wrestling and performing gymnastic feats on cables stretched across the river. The elders retired to the bathing pool for a morning soak.

Like a band of hirsute humans, the monkeys eased slowly into the hot water. They spend their nights in nearby trees; I can only imagine that the bath feels wonderful when dawn arrives.

I am not a wildlife photographer, but they did make an irresistible sight. Having arrived early, I was able to snap some clean shots. That opportunity quickly slipped away. Forty-five minutes after the park opened, an expanding ring of photographers encircled the bath.

The crowds would only grow as the day progressed. Once the tour buses arrived, the competition for position around the bathing pool would be fierce.

Of course these daily encounters with the paparazzi are no novelty for the snow monkeys. Like jaded movie stars they maintained a lofty indifference to the camera-clutching crowd. Since the monkey troupe does roam freely among the human visitors I would imagine that interspecies conflicts still pop up, but everyone was on their best behavior during my visit.

As odd as it might sound, the Jigokudani Monkey Park was one of the highlights of my Japanese expedition.

Book News

Book of the Month

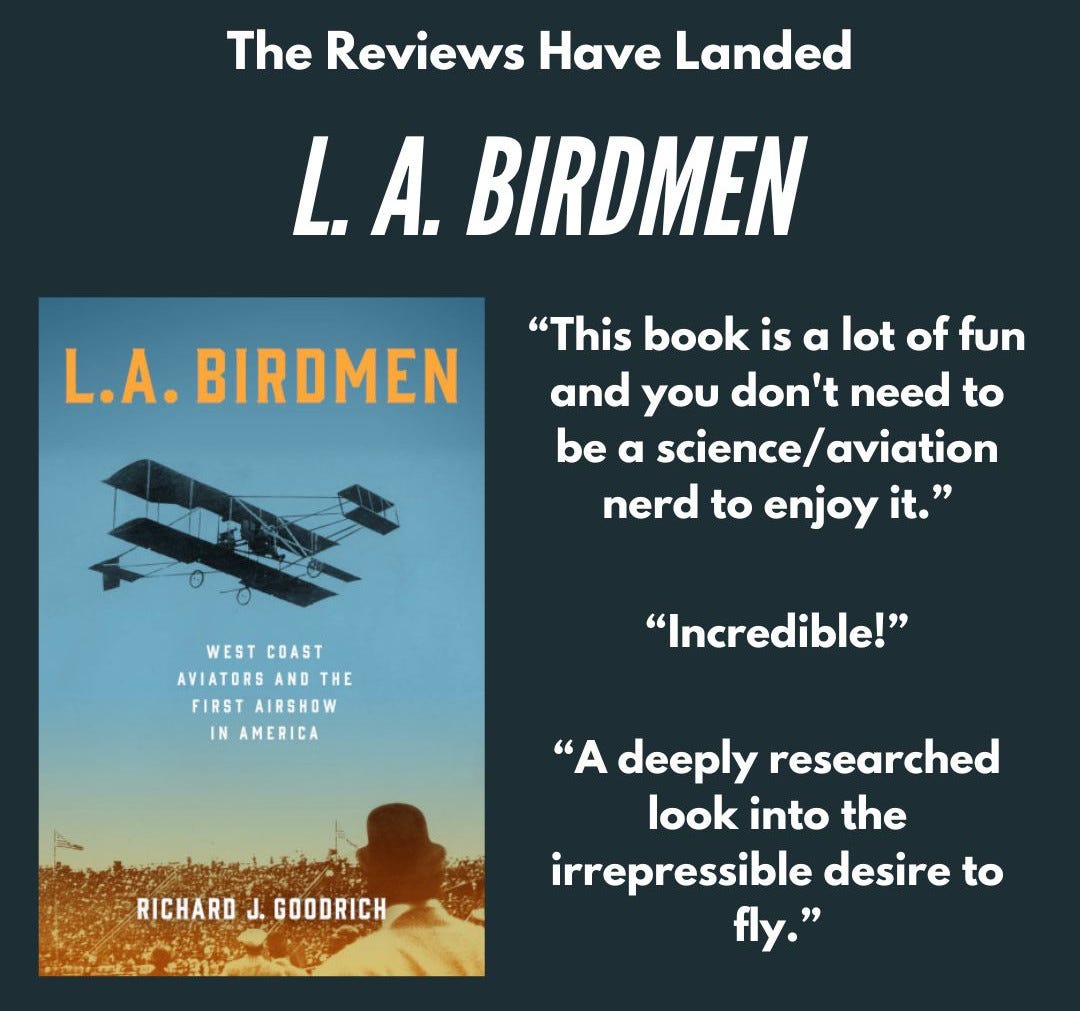

Britain’s Aeroplane Monthly chose L.A. Birdmen as its February Book of the Month:

[L.A. Birdmen] is engaging, at times whimsical, but always eminently readable, and brings to life the story of American flying with a great deal of detail and some wonderful asides. -Denis Calvert, Aeroplane Monthly.

Culture: The Mandarin Road

The publication of this month’s installment of the Peripatetic Historian coincides with the end of my second semester of intensive Mandarin. For the past six months I have spent 15 hours per week in a class at the Taipei Language Institute struggling to acquire a rudimentary knowledge of one of our planet’s most difficult languages.

The US Foreign Services Institute, which provides language training for the country’s diplomatic corps, ranks Mandarin as a “Category IV” language. It is a form of communication that will demand approximately 2,200 hours (84 weeks) of classes before a native English speaker acquires a reasonable level of communication competence. Contrast that with Italian—a truly lovely language—which can be embraced in a mere 552 hours (roughly 24 weeks of class).

My experience supports the FSI claim—Mandarin is a brutally difficult language and, despite averaging 25 hours a week in class and independent study, I have made far less progress than I would have expected. After a diligent struggle, I’ve come to the conclusion that vocabulary acquisition may be the greatest difficulty a learner faces.

There is the well-known fact that Mandarin is a tonal language and words that sound the same are only distinguished by the tone that is applied to them. A first tone word like mā means “mother;” the third tone mǎ means “horse.” This subtle difference provides many opportunities for confusion, but I knew this would be true before I started my training.

What I didn’t realize is that words can have the same tone and the same pronunciation but mean completely different things. In Mandarin the word pronounced yào means “to want;” it can also mean “to cost,” “to need to,” “medicine,” a “sparrow hawk,” the “upper section of a boot or sock,” “brilliant,” and “glorious.” How do you distinguish between these options? Context.

The other major obstacle is the writing script. Language learning theorists emphasize reading as the golden road to vocabulary acquisition. That works well with a phonetic language—where you can sound out words based upon the alphabet—but Mandarin’s pictographic system of representation further slows the student. It is not enough to learn the word—you must also learn the character that corresponds to that word. And to this Mandarin neophyte, those characters are often distressingly similar.

I could write an entire newsletter about the difficulties of learning this language. After six months of hard work I have probably only achieved a mid-A2 level—advanced beginner—in Mandarin. I am able to engage in extremely rudimentary conversations, but after a great deal of effort and study, my ability is frustratingly limited.

As this semester finishes, I am suspending my studies. The question of whether we will spend next year in Taiwan has yet to be resolved. If it looks like we shall return I may take some more lessons. On the other hand, I may decide that a rudimentary knowledge is more than adequate for my needs and leave it there.

Stay tuned…

Back in Taipei

We returned to Taipei in the second week of February. Our time in Japan offered far more experiences than I have recounted here, but the newsletter is beginning to stretch toward novella length.

To summarize: we enjoyed our stay in Japan. It is a fascinating country, filled with history. I could easily envision living there for an extended period.

For the moment, however, it is back to an exploration of Taiwan and whatever interesting experiences the coming months hold.

I hope all is well with you. Be safe, be sensible, and I will see you next month.

This newsletter was designed to be passed along to a friend. Hit the share button and send a copy to someone else who might find it interesting.

Thoughts? Comments? I have a button for that as well:

I hope you have healed from your manhole fall. The snow monkeys sound delightful. I wouldn't have attempted Mandarin so bravo. Hello to Mary!