Hello and welcome to the April issue of the Peripatetic Historian. I’m your host, Richard J. Goodrich, and once again we gather to weave history, travel, and photography into a coat of many colors. If you’re not sure what this is, or whether you want to continue the journey, there’s a handy unsubscribe link at the bottom of the page that will pop you out faster than an F-16 ejection seat.

On the other hand, if you’re ready to get started…

Peripatetic Field Report: In the Garden of the Generalissimos

What is the best way for a nation to handle a history that many would rather forget?

The Romans practiced damnatio memoriae (lit. the “condemnation of memory”). After the fall of a tyrant or the death of a disgraced emperor, the state could choose to chisel that person out of the historical record. Statues were destroyed, laws repealed, and official records altered.

They attempted to cleanse their history, sluicing away a painful past.

The urge to sanitize is not restricted to Rome. The question of how to deal with the reminders of the Civil War still divides the United States. Many would happily melt down statues of Confederate leaders and consign their battle standards to the flames.

Taiwan suffers from a similar division. For the first 26 years of its existence the country was ruled by Chiang Kai-shek. A hero or despot, depending on where you stand on the political spectrum, the general’s mixed legacy has produced a mild form of damnatio memoriae. In 2006, after the Democratic Progressive Party came to power, the government launched a series of initiatives to efface the departed leader from the country’s history. Chiang Kai-shek International Airport became Taoyuan International; debate continues over whether to rename the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Gardens.

The Generalissimo poses a problem; the country is seeded with visible reminders of the former strongman. During his tenure, an estimated 43,000 statues were cast and planted in public spaces across the country. Every park, police station, and military base hosts a reminder of the country’s leader.

Many of these statues remain in situ; some have been destroyed. But other examples have been relocated to a small park near Daxi, southwest of Taipei. Here, at the foot of a bamboo-shrouded hill, we find a thoroughly unique approach to the past: the Garden of the Generalissimos.

Workers have uprooted hundreds of statues and transported them to the park. There, on the banks of a crescent moon-shaped lake, the relocated images stand at attention in lines, formations, or simply small groups communing with one another.

It is even possible, for those who still esteem the departed leader, to share a picnic lunch with him:

The garden moves the needle into the red zone of the surrealism meter. Wandering through hundreds of manifestations of the former leader is a distinctly odd experience. On the other hand, it must be admitted that the Taiwanese have produced an adroit approach to the problem of the past. The forced relocation has reduced Chiang Kai-shek’s public presence, while simultaneously preserving a reminder of his legacy. Visitors are encouraged to contemplate—while not necessarily endorse—the memory of the former president.

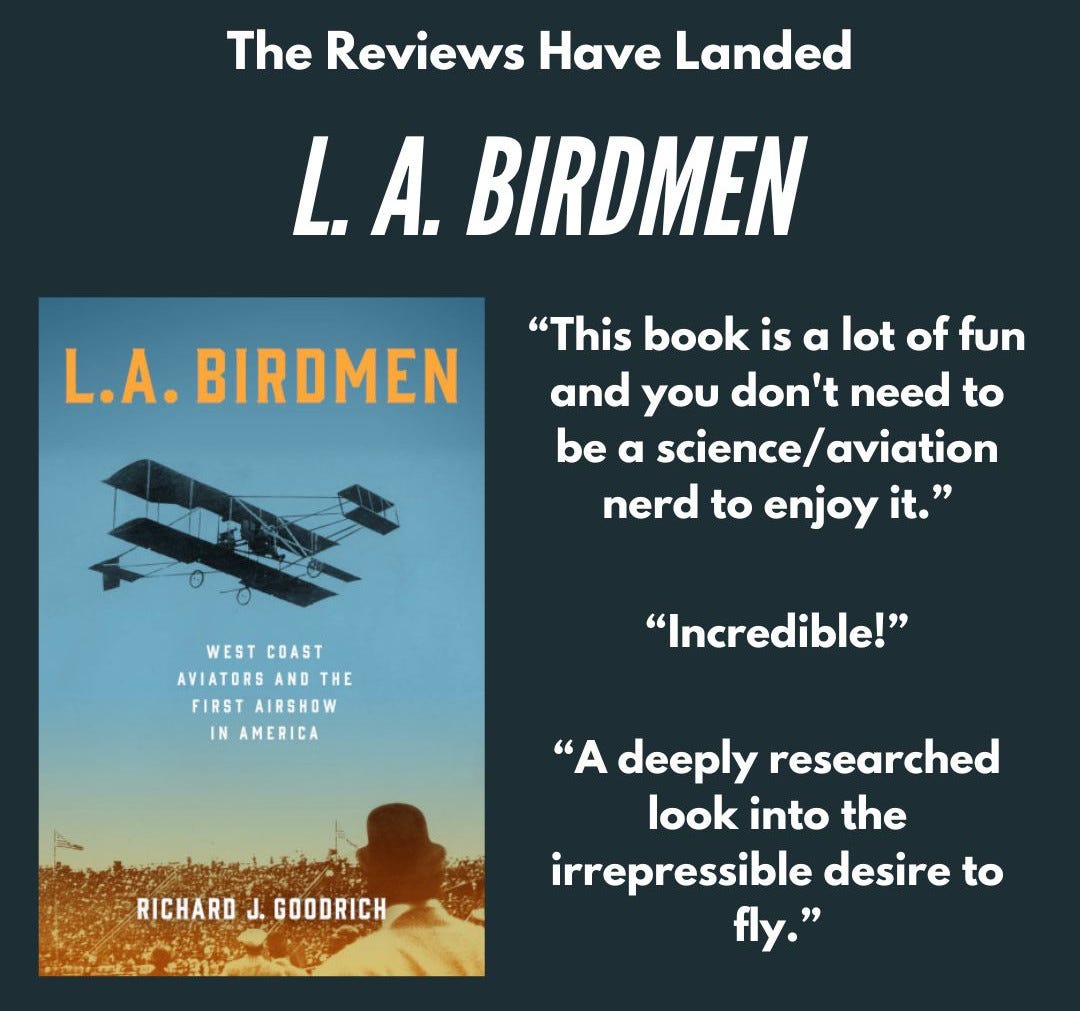

Book News

Chatting with History Nerds United

This month features a podcast interview with Brendan Dowd of History Nerds United. We discussed early aviation and L. A. Birdmen.

I normally can’t bear to listen to myself speak, but this one sucked me in. Brendan is an engaging interviewer and our discussion devolved into some witty (sophomoric?) repartee that held my attention to the end.

Highly recommended.

The Head Relics of Xuan Zang

Sun Moon Lake is one of Taiwan's best-loved tourist destinations. Standing at 3,300 feet above sea level, the small body of water cuddles in the mountains east of Taichung. When the lower altitudes begin to swelter and steam, people flee the cities for this vacation paradise.

Or, if you’re like me, you visit on a drizzly, off-season March day.

We stepped off the bus in the tiny resort town of Shuishe. Bicycle hawkers huddled before open garages of two-wheeled steeds. Desperate voices called as we strolled past, extolling the joy of cycling beneath a steady rain.

Not interested.

Instead, we caught one of the small ferries that shuttle passengers across the lake. There, on a hill that commanded the southern shore, was Sun Moon Lake’s finest attraction: the Xuanzang Temple.

Xuan Zang was a Chinese monk who lived at the beginning of the seventh century. After joining a Buddhist monastery, the young man grew disillusioned by the lack of consistency among his country’s teachers. Every abbot taught something different about the religion, and the true message had vanished behind the overgrowth.

The monk decided that his religion required a good pruning. He set off on a journey to India, hiking across China to the source of the “Buddhist Dharma” — the authentic teachings of the master.

He spent seventeen years studying in India and then returned to his homeland. Isolating himself in a monastery, he composed an epic account of his pilgrimage (the Record of Western Lands) and is said to have translated 1,335 Buddhist treatises into Chinese. After decades of work and several million words, Xuan Zang passed away at age 64.

During World War II, the Japanese discovered Xuan Zang’s relics in Nanjing, China. Recognizing the pilgrim-scholar as an important precursor of Zen Buddhism, they transferred his bones to Japan.

In 1955, after benevolent discussions, Japan offered to return half of the relics. An honor guard of Buddhist monks escorted a piece of the skull—the “head relics”—to Taiwan. Ten years later, the Xuanzang Temple was completed and the relic was placed on permanent display.

The precious remains rest in a brass urn on the third floor of the temple. Visitors are not allowed to approach the vessel, but a camera mounted inside the urn transmits live images to two video monitors mounted at the back of the room. Since no one expects a sudden change in the bit of bone, I don’t know why we need live surveillance. Perhaps television is just more “real” than a photograph.

In an adjacent building, an informative museum details the highlights of Xuan Zang’s career. I have not hiked as many miles nor written as many works as the peripatetic scholar, but I did feel a certain kinship with him. Those of us with a peripatetic vocation must stick together.

The temple was the highlight of my visit to Sun Moon Lake, a place of words, walking, and the sound of a gentle rain slipping through wet cedars.

Moving Ahead

I’m sure you remember the old adage: April showers bring May flowers. As I ink in the final strokes on this month’s newsletter, torrential rains wash the streets. I’m not certain what that presages: April monsoons bring bassoons? Raccoons?

Perplexing. I’ll monitor the situation and let you know what happens.

Be safe, be sensible, and I will see you next month.

Know someone interested in history, travel, or bassoons? Hit the share button and send them a copy of the Peripatetic Historian.

Thoughts? Comments? I have a button for that as well: